Any research into the theory of training and you'll likely stumble across the same three models. The General Adaptation Syndrome Theory, The Fitness-Fatigue Model, and a variation of the Stimulus-Fatigue-Recovery-Adapatation theory. For most of us, we've probably at least stumbled across one, or all, of these throughout our time learning about S&C and Sport Science. Honestly, despite seeing these over and over again I never really understood why they kept coming up. Every time they were presented I felt like it was always the same thing said for all the different models: "Training is a stress stimulus that causes fatigue and once you recover, you're better".

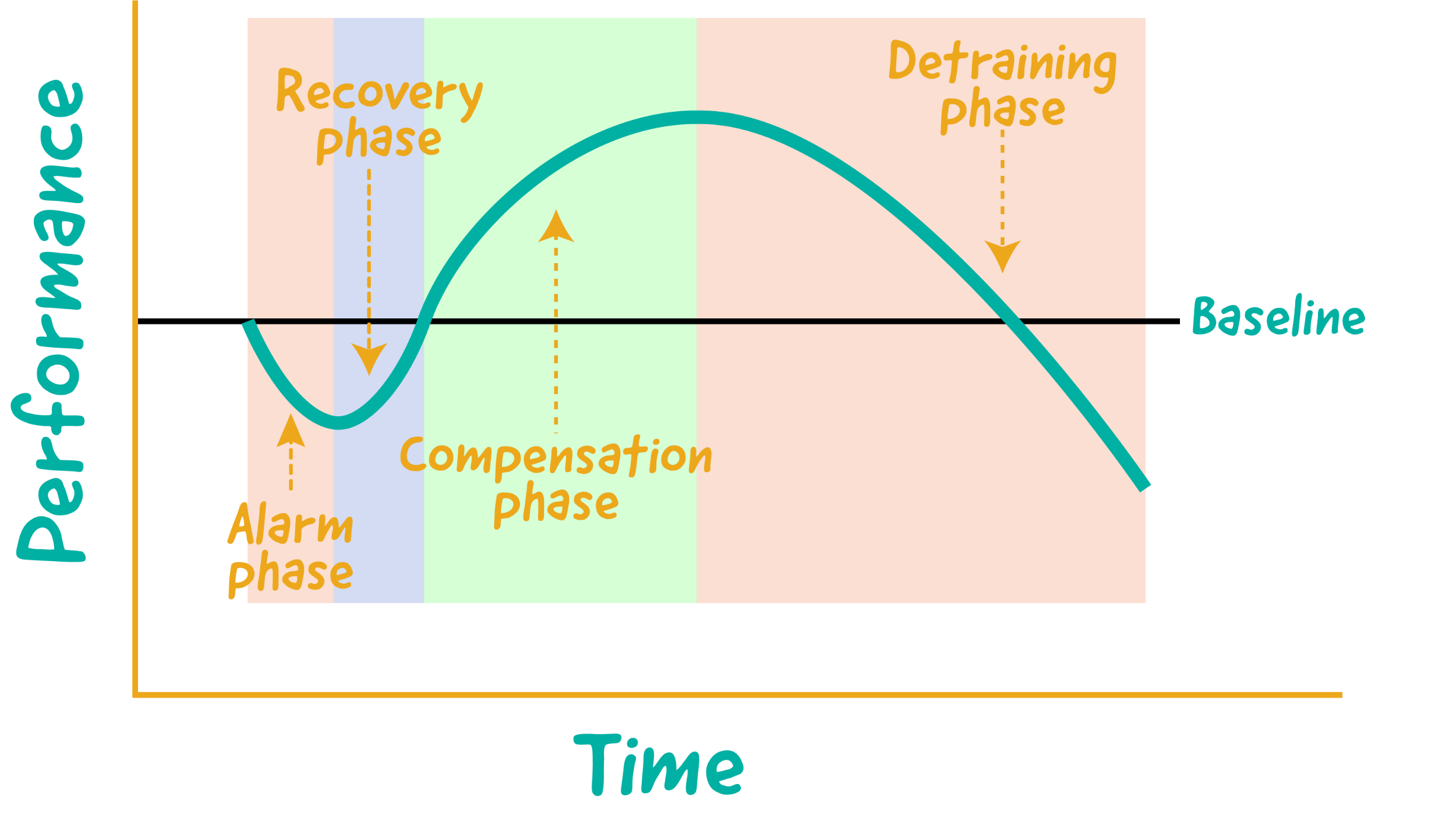

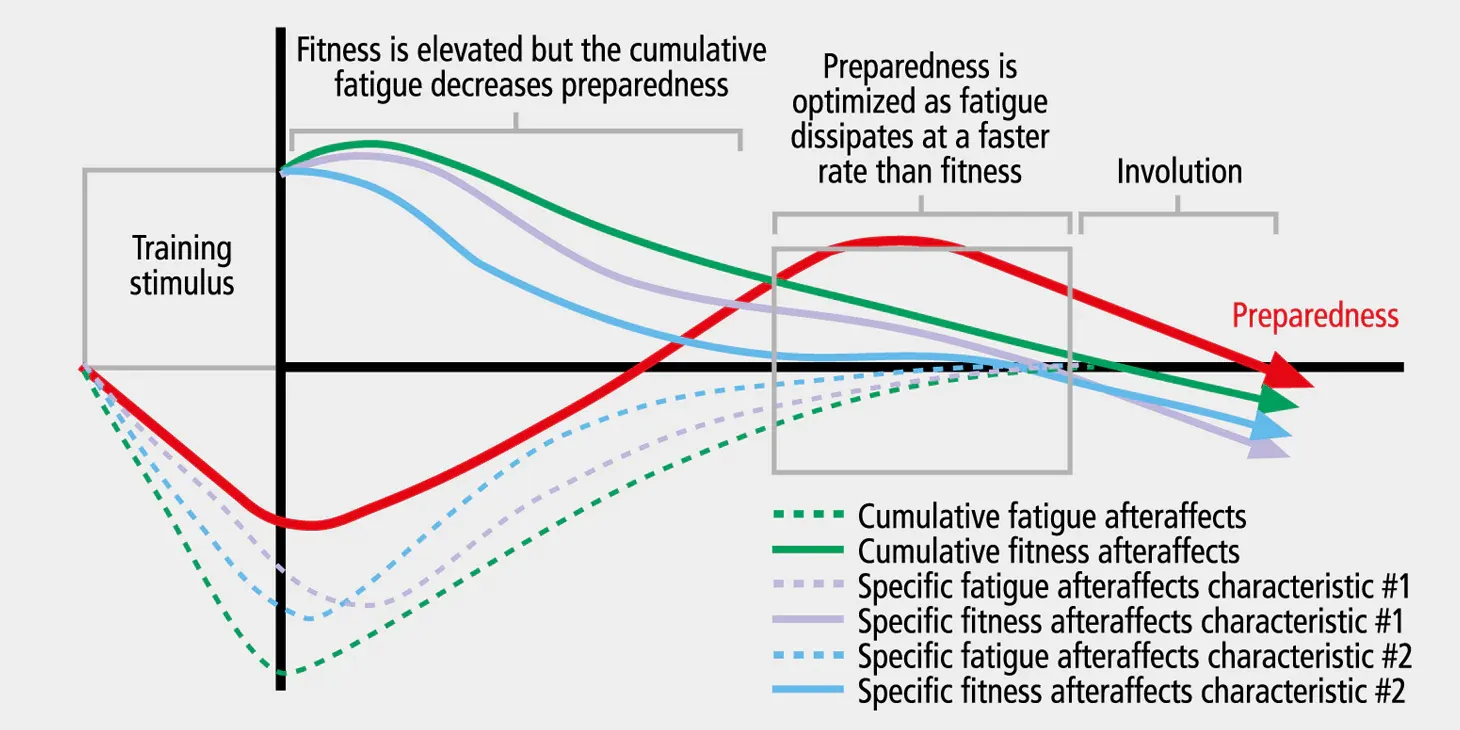

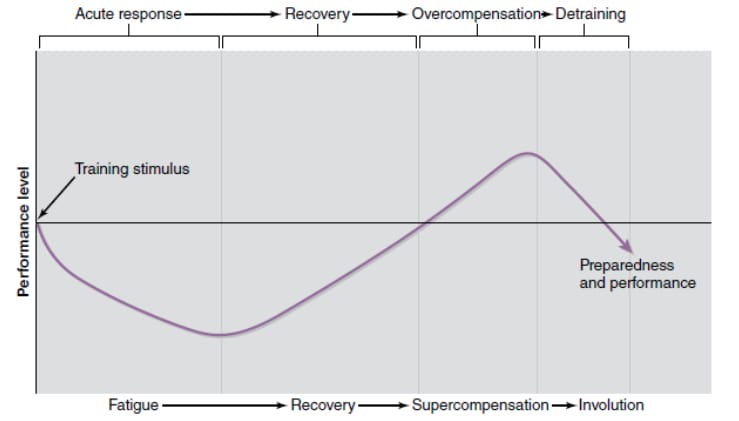

It wasn't until reading Dan Cleather's The Little Black Book of Training Wisdom that I saw this presented in a novel way. If we look at the above images we see that the dynamics of performance capability are essentially the exact same for every model. In all the images the line represents our performance level (this is the red line called preparedness in the fitness-fatigue model picture). Ultimately they all say we train, then there is a reduction in our performance capability, then we recover above baseline, and we are now the proud owners of improved performance in whatever we were training. However, as Dan suggests in his book, these are not just different ways of saying the same thing. Instead, they suggest different mechanisms for performance enhancement. Let's zero in on our first two models, as they are probably the most often cited in S&C material.

The GAS model applied to performance suggests that the training stimulus causes an immediate reduction in our ability to perform. It is necessary therefore for a period of recovery and subsequent adaptation to take place before we see any improvement in performance above baseline. On the other hand, we can see that the fitness-fatigue model suggests almost the opposite. That our ability to perform the task that we have just been training is actually immediately improved and it's only the result of fatigue masking our new ability that our performance capability is depressed following training. Contrary to the GAS model, it suggests that there is no need for adaptation to see performance improvements. Dan gives this a novel concept handle called the "practice model" of training and argues that these two mechanisms suggest the idea of tangible vs. intangible adaptations to training.

If we look at this practically, a GAS-centered approach to training theory infers a more tangible adaptation style. For example, when we train we cause some metabolic and/or mechanical damage to the muscles used and it is not until these muscles recover and display some positive adaptation such as increased cross-sectional area or improved muscle architecture that we see an enhancement in performance. Whereas, a practice model approach based on the fitness-fatigue model infers more intangible adaptations, which are often the result of neural adaptations. For example, with each rep practiced of the squat, we improve our ability to squat due to something like intra-and inter-muscular coordination or the disinhibition of inhibitory mechanisms. This brings Dr. Cleather to one of his main arguments in the book - "Fatigue is not a necessary outcome for training to be effective."

This idea that we can improve performance by "practicing" training makes inherent sense to sports coaches but I think it's often lost on "evidenced-based" practitioners (read lab coats) who are overly preoccupied with physiology. Coaches intuitively understand that if you ask an offensive lineman to go out and practice board drills on air, it probably doesn't present much of an appreciable amount of fatigue but they will certainly be better at their footwork. Training doesn't always need to be hard and/or always focused on making adaptations to things we can easily see or measure. I think our own training and the training of our athletes could be improved if we add the practice model of training to our mental maps of S&C.

In a future post, I'll touch on the dangers of relying too heavily on training theory models, in the meantime consider adding some practice days to your physical prep.

Nelly

Member discussion: